Rinds: What are we drinking to?

A strange cocktail encounter in Daniel Immerwahr's Book, How to Hide an Empire

What follows is a recipe for a cocktail. It’s from the year 1898 and it’s named after Rear Admiral George Dewey, the American naval hero of the Battle of Manila in the Spanish American War.

It doesn’t appear in Around the World with Jigger and Spoon or The Savoy Cocktail Book, or any other classic source materials of cocktail revivalism. I didn’t have it on a popup menu at Death and Co. or Thunderbolt. Instead, it came up while reading Daniel Immerwahr’s book, How To Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.

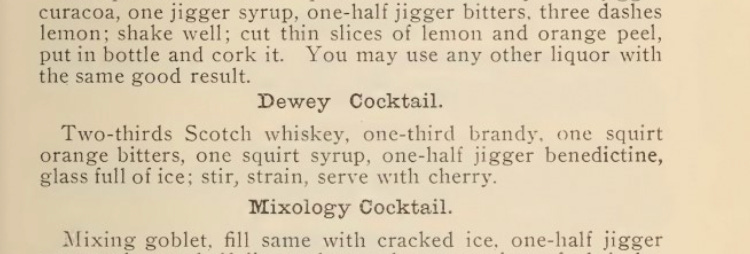

“The Dewey” goes like this.

Did you learn about the Spanish American war when you were in school? Did you study for a question about the Monroe Docrtrine for your AP US History test? Perhaps you’re as undereducated as I am about this period of American history. Perhaps you are also as overeducated as I am about classic American cocktails.

Humor me a little bit of history and we’ll get back to drinks in a minute.

In 1898, Commodore George Dewey led the US Navy’s invasion of the Phillipines during the Spanish American war. To help dislodge the Spanish from Manila, Dewey’s navy collaborated extensively with nationalist Filipino guerillas led by Emilio Aguinaldo, promising Aguinaldo that the US would commit to Philippine independence once the war was won.

Suprise: after ousting the Spanish, US forces instead turned their guns on Aguinaldo’s independence movement, killing thousands and seizing the entire archipelago as an American territorial holding, which they held until 1950. According to Immerwahr’s math in Empire, the US military subjugation of the Philippines between 1898 and 1903 claimed 750,00 lives, greater than the human losses of the Civil War.

Immerwahr’s book follows 300-odd years of American aventures in colonialism, with special attention (and granular human detail) to America’s colonial expansionism in the first decades of the 20th century, where places like the Phillipines, Guam, Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, and Cuba (and American Samoa!) fell under American influence and occupation. In short: this book is full of racist, paternalistic old fucks like Admiral George Dewey.

And while it’s not full of cocktails, the history of America’s 20th century colonial empire is well-stocked with their ingredients: sugar and rum, oranges and key limes. Cocktail culture of the age is littered with the characters and settings of Empire as well.

While Deweys and Roosevelts were shooting up the tropics and planting flags, private clubs and hotel bars on the “mainland” were using mixology to historicize and lionize these violent achievements of empire and the political actors associated with them.

Cocktail books and bar ephemera throughout the “Gilded Age” period are littered with recipes recalling specific military events and characters from this period. Enduring or revivalist classics like “Remember the Maine,” “The Commodore,” and “Cuba Libre” were originally christened to celebrate American military incursions on Pacific and Caribbean soils.

Hemingway is here, too. From his long-suffering barstool at Havana’s La Floridita, he could have waved a finger in the direction of Daiquiri: it’s the name of the beach where Teddy Roosevelt’s rough riders first came ashore to oust the Spanish and establish military (and later, economic) occupation of Cuba. It’s also where a wealthy American merchant named Jennings Cox, famous for popularizing the cocktail, owned an iron mine. Sexy.

Luckily the “Dewey Cocktail” discussed above tastes like ass and therefore didn’t make it out of the 20th century. But you could see it in a Punch Drink headline, couldn’t you? Drink like a Gilded Age Rear Admiral with [this bar’s] riff on the Dewey Cocktail. A bracing half-ounce of benedictine gives this stirred libation….

Look. Not everyone who raised a Daiquiri or a Dewey at the dawn of the 20th century was actively toasting white supremacy and colonial violence– though many, Hemingway and Teddy Roosevelt among them, certainly were. Many more were probably just good liberals like you and me, trying to take some small delight in the latest boozy trend, or to support their barkeep friends at their new gig, or to generally take the edge off in edgy times.

But what is true, I think, is this: Our patterns of consumption form a ledger of the historical moment in which they were conceived. Drinking culture in particular is full of cultural memory.

And what is useful to consider, I think, is this: As we pour each other drinks today, what evidence of our current psyche, of our cultural moment, are we leaving behind for future generations to rediscover us by? What traumas and hubris, what colonial extractions, are preserved in the endless march of the drinks of summer, our beer brand identity politics, our celebrity tequila?

What are we putting to our mouths right now that will make a historian in 100 years read through our bar tab and say “yikes,” the way I did when I heard about Dewey? What, we should ask ourselves, are we drinking to?